Welcome to the world of wings and wing venation. The following may make your head hurt!

The wings of bugs have evolved in a multitude of ways and are one of the main things that are used to define the orders of insects. Coleoptera (beetles) for example have modified their front wings to form a tough shell, known as the elytra, that cover and protect the membranous hind wings beneath. Grasshoppers, among others, have have toughened their forewings into leathery but still wing-like covers called tegmina. And Diptera (true flies) have lost their back wings altogether and evolved balancing organs, known as halteres.

Fortunately many insects have the good grace to display patterns on their abdomens, certain overall colourings or some other identifying trait that makes working out which species they are relatively straightforward. However, with some bugs that have retained membranous wings the veins within them are often the only way to tell the difference between species. These are relatively few in number but there are many more where the pattern of veins in the wings, or wing venation as it’s properly known, is an important pointer towards a positive id. Therefore an understanding of wing venation is a definite advantage when it comes to identifying certain insects, especially flies and wasps.

Ok, I’ll do my best to keep this simple…

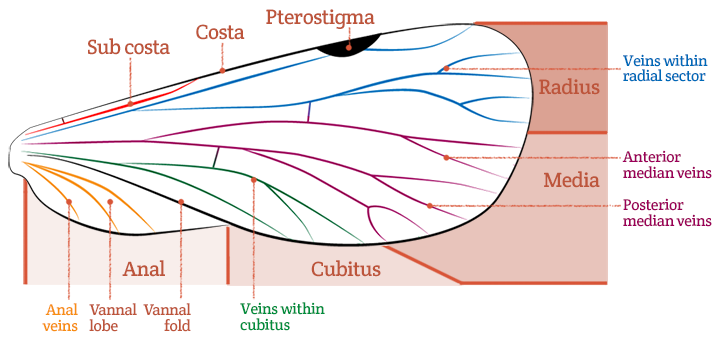

The main veins in an insect’s wing run longitudinally (ie from near the body towards the wing tips) but frequently fork off into branches and this is where confusion can (and does!) occur. These main veins are connected by short cross-veins. Generally it is the main veins that you’ll be looking at but the cross-veins can be important. To help when discussing wing venation a system of naming and numbering has been developed that divides the wing and its veins into sections, going from front to back. To illustrate, here is a fictional insect wing showing those parts, but bear in mind the venation is often simpler than this:

The front edge of the wing is called the costal margin and the main vein running along it is known as the costa. The next vein that sits directly behind it is the sub costa and can be longer than shown above. In some insects there is a darkened patch on the leading edge of the wing and this is the pterostigma which can sometimes be diagnostic. The next main set of veins (behind the sub costa) fall into the radial sector and the first of these veins is called the radius or R1. The veins that run trough the mid section of the wing fall into the media, the first set of veins being the anterior median veins and the second set the posterior. Below them comes the section known as the cubitus. On some (but by no means all) wings there is then a fold along which the wing flexes in flight and, if present, is known as the vannal fold. The resulting bulge is called the vannal lobe. Finally the bottom edge of the wing is the anal margin and the veins that come after the cubitus and lie towards the body are the anal veins. (No sniggering please).

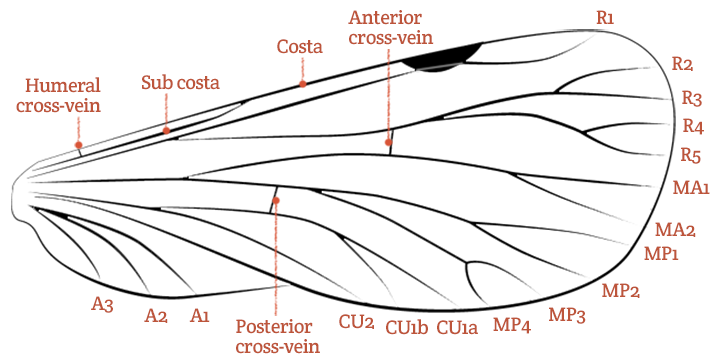

All these veins are labelled and the numbering relates to each main vein in turn plus its branches, which looks like this:

To explain (or complicate – depending on how you look at it) a bit further, the main leading vein, or costa, is never branched and is also known as C. The sub costa can sometimes be branched and if so the veins are labelled SC1 and SC2. The radial sector always starts with R1 and this can fork off to one or, as shown above, two further branches. It is the sub-branches nearest the wing tip that are numbered – in this case R2 – R5. The next main vein, the media, can be forked. The first main branch (nearest the body) is the anterior division and its sub-branches are labelled MA1 and MA2. The next branch is the posterior division which can again fork twice, as above, the resulting sub branches being MP1 – MP4. Then comes the cubitus and the top (or to use the jargon again, anterior) off-shoot can divide in which case is labelled CU1a and CU1b – but if it doesn’t split it’s just called CU1. The lower (or posterior) branch of the cubitus never splits and is CU2. Finally there can be up to four anal veins which never fork and are numbered A1 – A4. (As you can see I only used three in my diagram.)

Often these veins are connected by any number of cross-veins (generally the more cross-veins, or veins generally, the older the insect is in evolutionary terms) but only two are commonly referred to. These are the anterior cross-vein, which always joins the radius to the media and the posterior cross-vein that always joins the media to the cubitus. Sometimes the humeral cross-vein is mentioned, connecting the costa to the sub costa, so I also put that on the diagram!

And breathe…

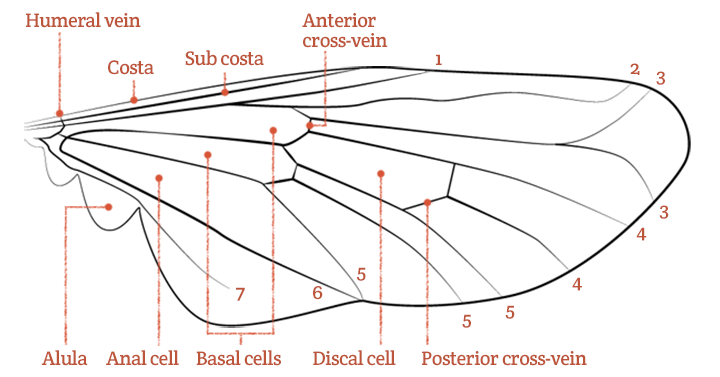

Well, as you will have worked out if you’ve read the general anatomy page, entomologists are an awkward bunch of so-and-sos and it will come as no surprise that dipterists (fly fanatics) and lepidopterists (butterfly lovers) have a different way of doing things. They only number the main veins – the forked branches having the same number as the main vein they’re attached to – and it can get a bit tricky when working out which bit of vein belongs to which. So deep breath and here we go again with a made-up fly wing:

The costa and sub costa are the same as before and vein 1 is the equivalent to the radius already mentioned and is pretty easy to find. The next couple of long veins are again fairly obvious and you can see that where vein 3 splits into two the offshoots are both labelled 3. The anterior cross-vein then comes in handy as it always joins veins 3 and 4. Many insects, not just flies, have a discal cell which is a variably shaped area bounded by veins near the centre of the wing. The anterior cross vein generally runs off its top edge. It can get a bit messy here but the posterior cross-vein can help us out as it joins veins 4 and 5 – if you can work out which it is! Veins 6 and 7 are the anal veins and again a little easier to spot. The shape and size of the basal cells are often important when identifying flies and if there is an anal cell it will be found behind – remember we’re running from front to back – the basal cells. Some flies have bulges on the rear edge of the wing nearest the thorax and the largest of these is called the alula. And finally the humeral vein is a tiny little thing which can occasionally prove useful in identification.

I’ll admit it took quite a while to get my head around all this, and I still have to remind myself often, but I hope you’ll have a better idea of what to look for when some book or other wanders off into the wonderful world of wing venation.

Recent Comments